Stay in the know

Get updates on managing achondroplasia, ongoing research, and stories from others in the community.

a type of skeletal dysplasia (a condition that affects the bones and cartilage). While the most visible effects are in the arms, legs, and face, nearly all of the bones in the body are affected. This condition can cause serious, progressive, and lifelong complications. Despite these complications, achondroplasia does not have to hold people back from living happy and fulfilling lives.

The more you know, the more prepared you can be for the future.

1 in 25,000 children are born with achondroplasia, and there are about 250,000 people in the world with this condition.

Most children with achondroplasia (80%) are born to parents of average stature as the result of a change in the gene (a variant) that causes it to not function properly.

Sometimes achondroplasia is diagnosed before birth based on physical features during a prenatal ultrasound. Radiology (medical imaging) may be used to confirm the diagnosis. In other cases, it isn’t diagnosed until after birth.

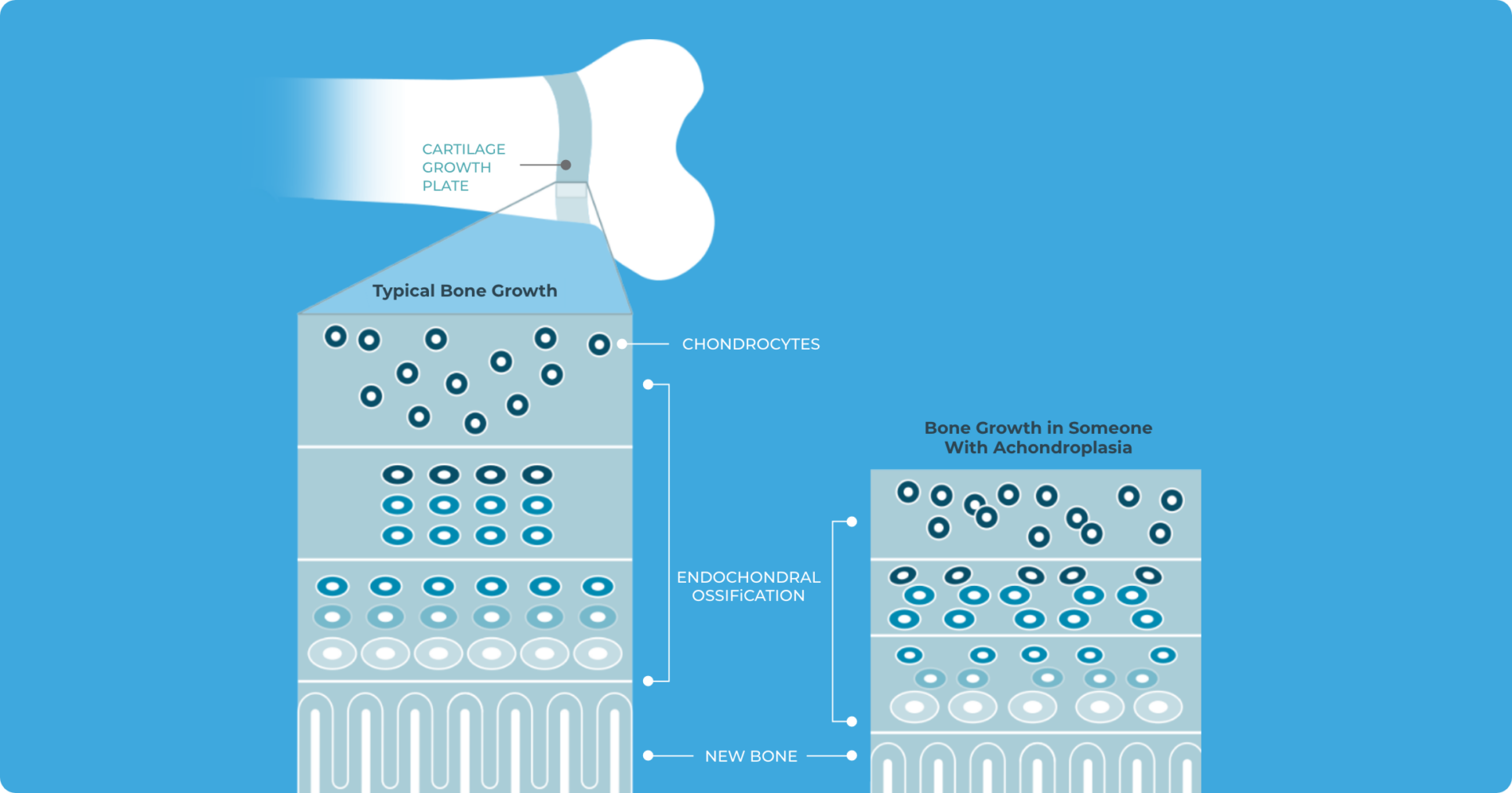

Bones begin growing before birth (in utero) and keep growing until adulthood. The process happens in the bones’ growth plates, where the body makes cartilage that is then replaced by bone.

Chondrocytes (cells in the cartilage) line up to form new bone. This process is called endochondral ossification and happens in almost all the bones of the body. Receptors in chondrocytes control the process by sending out and receiving signals.

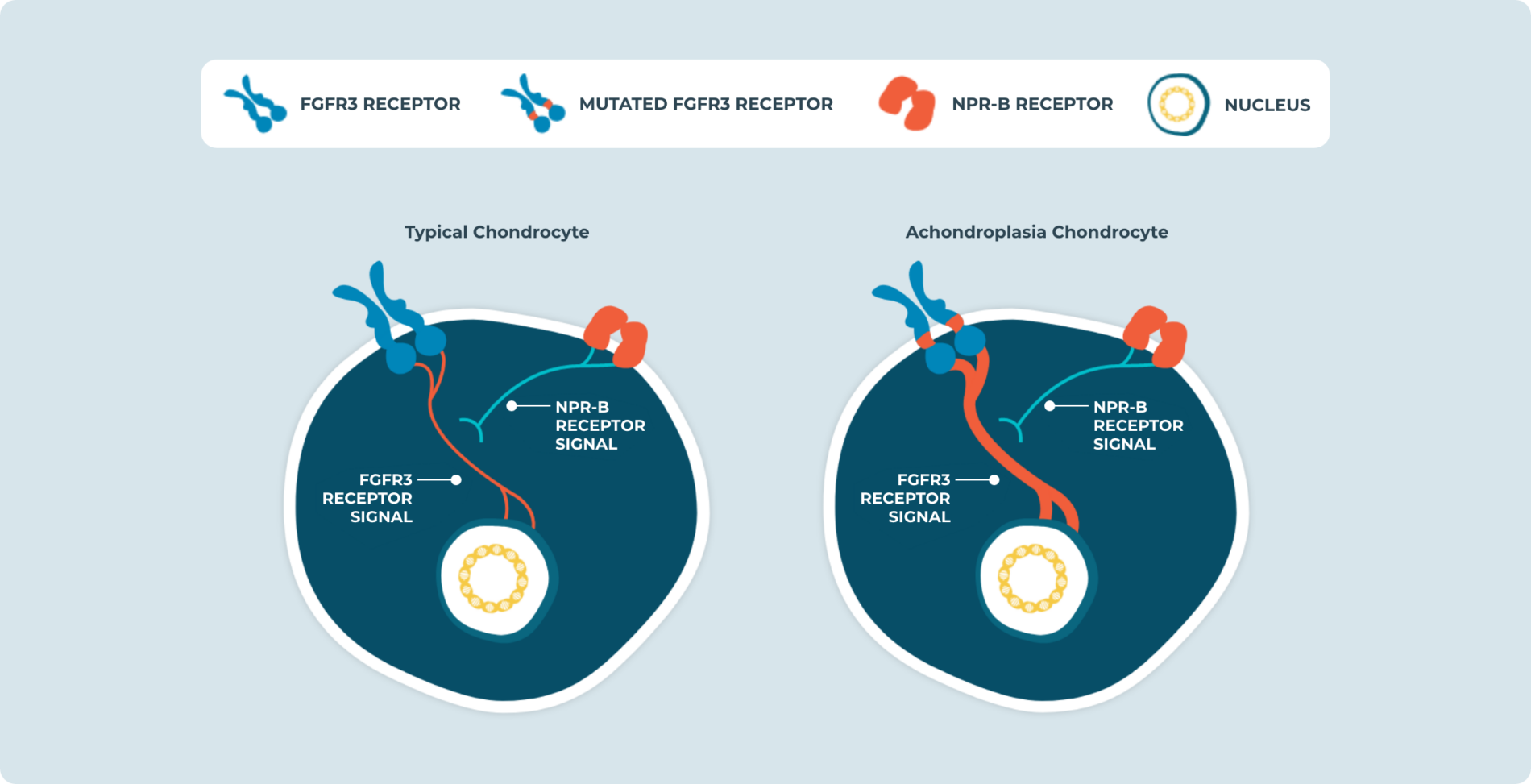

Some signals, like the signals from FGFR3 receptors (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3), tell the bones to slow down growth. Others, like the signals from NPR-B receptors (natriuretic peptide receptor-B), block those signals and allow bones to grow.

FGFR3 receptors are usually only “turned on” when the body needs to stop changing cartilage into bone.

In achondroplasia, a change in the structure of the FGFR3 gene causes the body to continuously send out signals to slow bone growth. Because FGFR3 receptors are always “turned on,” the signals to slow bone growth are stronger than the signals that tell bones to grow (which come from the NPR-B receptors).

As a result, the chondrocytes have trouble lining up to form new bone, impairing bone growth.

From going to school to playing with friends, children with achondroplasia can lead healthy, active lives.

At the same time, because of the way their bones grow, physical complications can occur and progress over time. But if you know what to expect, you can help your child focus on the most important thing of all—just being a kid.

Get updates on managing achondroplasia, ongoing research, and stories from others in the community.